I listened to the blues and watched ballet the night they fed the dead guy to the alligators.

The Jackson Ballroom was in Houston’s Fifth Ward on the banks of the Buffalo Bayou. The big windows to the left of the Ballroom’s stage framed the skyline of the city. When I arrived that night, the internal glow of Houston’s downtown towers had started to outshine the glow of the sun setting behind them. The windows were open to capture any breeze in the humid night, but the air in the room moved mostly because of ceiling fans. The musty scent of the Bayou complemented the century-old patina of the ballroom.

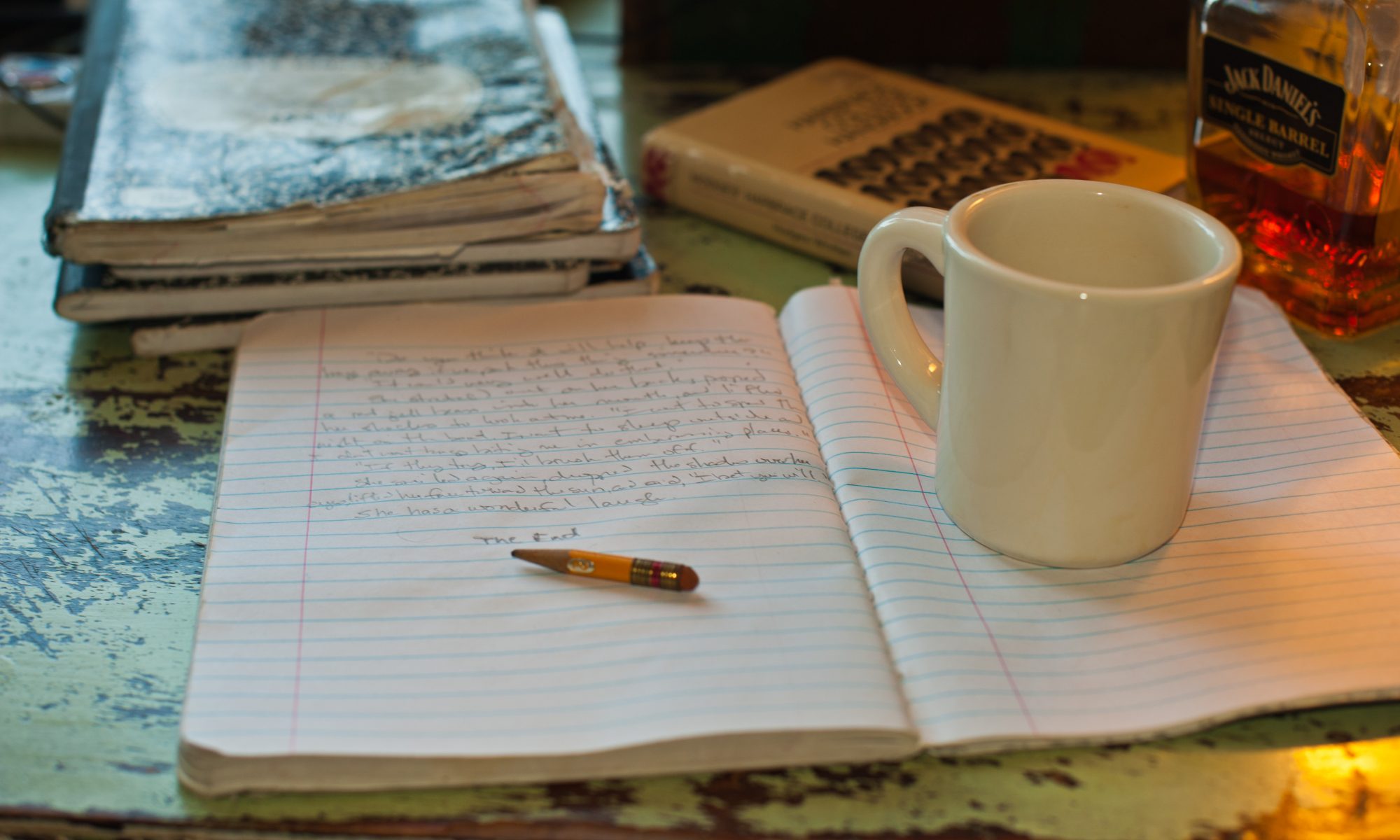

A hot Friday night in June was perfect for slowly sipping a whiskey while listening to the blues, but I was there to see a client. As I walked in, I caught the eye of the bartender, Jake, and pointed at the coffee pot. He nodded. A few minutes later he brought me a mug of strong coffee laced with chicory. I wrapped my hands around the mug and breathed deep. The dark and rich scent of the coffee gave me goosebumps of anticipation. I sat back to enjoy the music.

My client William “Thumper” Lee, an eighty-something-year-old African American, did not look my way. But I knew he’d seen me. Soon after I sat down, he traded his electric guitar for his battered acoustic six-string and started singing his composition “My Wife Called a Lawyer.” I know the song. The lyrics include a line, I called up my lawyer, he set a court date. That night, Thumper sang, “I called up my lawyer, he showed up late.”

Thumper finished the song and made his way to my table. I said, “Cute, but I wasn’t late.”

He smiled as he sat down. “Hey, Samuel, the lawyer man. Good to see you. You drinking coffee? Here? At this time of night?”

“You said you had some legal stuff to talk about. I thought I’d stick to coffee.”

“You’re coming up to the river with me, right? Hope so. I need a ride home. You came ready to spend the night like I said, right?”

“Yep, I’m ready.”

“Good. We’ll talk about the legal stuff up there. Have a drink.”

Thumper’s invitation to spend a couple of nights at his place on the Trinity River intrigued me. When I measured clients by the size of collected legal fees, Thumper was by far my best client, but we rarely socialized outside various blues bars in and around Houston.

Although invited, he’d never been to my place on Galveston Island. I’d never even been invited to his place on the Trinity River. I looked forward to the visit. The summer had a melancholy slowness, and visiting his place would be a welcome diversion. Besides, I enjoyed doing legal work for him. His legal stuff was different from my other work. Some time ago I gave up trying to convince him to find a lawyer who knew recording and performance contracts when he told me, “You did me pretty good taking on the company. I reckon you got me enough money to die with. I’m happy. I don’t much like lawyers, but you’re better than most. It ain’t about perfection, you yon zanmi, man. Yon zanmi.”

I had to look up yon zanmi. It means “a friend” in Creole. I’ve since heard it in the lyrics of a Zydeco song. It pleased me that Thumper called me a friend.

That night at the Jackson Ballroom, I said, “Let me get this straight. You had me come up here because you need a ride home? How’d you get here?”

“I had a ride. I need lawyer help. Right now, though, you’re about to see something special. You just wait and see. It has to do with what I need you for.”

He got up from the table and walked through the room, greeting a few people on his way to the door that led backstage. I admired the beer in frosty glasses sitting in front of the couple next to me. It was a hot night. I went to the bar and got one for me. After Jake handed me my beer, he came out from behind the bar with a push broom and started sweeping the dance floor in front of the stage.

The drummer, a white kid who looked about sixteen years old, started playing around on his drums, brushes shuffling on his snare with a rim-shot on the backbeat. The bass player, a skinny black guy known as Lefty Tom, got up from a table, picked up his upright bass, and started playing in time with the drummer, slowly walking the notes up and down. The percussive beat caused most everybody in the place to start keeping time with feet tapping on the floor or fingers on tabletops. Thumper returned to the stage, plugged in his electric guitar, and joined the percussive rhythms with chords, soft and slow and gentle.

Thumper said, “Now, you dancers out there, do me a favor. Sit this one out and just watch. You are about to see something special.”

He kept playing the unformed song and looked with irritation toward the corner behind me. There, at three tables shoved together, eight people were having a good time enjoying their drinks but not paying attention to the music. They tried to talk over each other, and noise from their table got louder and louder.

“Hey,” Thumper said. “Hey, y’all back there in the corner. Listen up.”

Several of us turned to look at them. One or two of their crowd poked the others and let them know they were being spoken to from the stage.

“Hey,” Thumper repeated. “I know y’all are having a good time. That’s a good thing. But do something for me. We’re about to have something special up here. Something you ain’t never seen here in the Hall. Keep it down, will you?”

The noise lessened. The crowd’s attention returned to the front of the house. The song took shape. I listened to a lot of Thumper’s music. I recognized the repeating chords of his song “She Walks On Water.”

Jake turned off most of the lights, leaving on those over the racks of bottles behind the bar, several small spots shining up against the wall behind the band, and a couple of spots making the dance floor the center of attention. Thumper started to sing.

She walks in the morning,

But you can’t see her cry …

A ballerina appeared from the backroom to a collective murmur of surprise in the room. She glided to the front of the stage balanced on her toes in that magical, ballerina way. She wore a cornflower blue bandeau top and brief shorts. Shimmering drapes of pale rose-red and white floated and flowed around her. Her skin glistened under the spotlights like silk. She was gorgeous. Not a sound came from the audience. She mesmerized us with her dance.

She walks in the morning,

But you can’t see her cry …

Thumper and the band played a little softer than usual. Everybody in the place watched the dancer. Even Jake. Jake was usually in constant motion. If nothing else, he polished glasses or wiped down the bar top. For this performance, he leaned with both hands on the bar and did nothing but watch the dance.

She walks in the morning most every day,

She walks all alone and nobody sees her cry,

She walks in the summer, the winter too,

She walks all alone and nobody,

No, nobody,

Sees the tears in her eyes.

I recognized the dancer. I enjoyed ballet. My Uncle Harlan, a benefactor of almost all performing art associations in Houston, shared his tickets to the performances. Plus, I occasionally went out with Carol Smithers, a vice-president at Texas Commerce Bank. Carol danced ballet from the age of two until she was seventeen. On our first date to a ballet, Carol told me, “When I was a junior in high school, my boobs grew too big to dance ballet. I was the only girl at my high school crying because her boobs grew.”

Harlan had a box where the performances were enjoyed from a distance. Carol’s tickets were up close. With her, I couldn’t see the entire stage at once and tended to focus on individual dancers. I heard more of the effort. I saw past the stage expressions and noticed the intense concentration on the faces of dancers. I saw the sweat. I appreciated the strain and focus. I noticed the dancers as individuals.

I recognized Angelique Cambray dancing to the blues of Thumper Lee that night. She was a soloist with the Houston Ballet.

Thumper’s trio made the song a little longer than usual by sticking a harmonica solo by Thumper in the middle. The soulful wail of the harmonica perfectly accompanied Angelique’s sensual movement. The music sped up during a guitar solo and Angelique’s body carved fast, graceful curves in space. Suddenly, the song slowed with the final lyrics.

Take pity on the girl,

I say,

Take pity on the girl.

She walked on the water in the morning,

She walked on the water,

And the river,

The river washed her tears away.

With the last two lines, Angelique sank to the floor, the multicolored drapes pooling around her. A tear coursed down her cheek. I’d seen ballet done to blues and jazz in the magnificence of Houston’s Wortham Theater accompanied by the orchestra. But on that hot summer night, in a century-old blues hall on the banks of the bayou with music provided by Thumper’s music, Angelique danced the most moving ballet I’d ever seen.

That was about the time they were cutting the dead guy into pieces for the alligators.

Angelique did a simple curtsy to enthusiastic applause and ran off into the back room. Thumper walked over to my table, wiping his face with a handkerchief.

“Thumper, that was one of the best things I’ve ever seen.”

He smiled. “Yeah, she’s something, isn’t she? She’s the reason you’re here.”

“Why? What’s up?”

“I done told you, we’ll talk about it later, up at the river. First, I want you to meet her.”

He went backstage. Thumper takes his own time to do things. Curious about what kind of legal help Angelique Cambray needed, I knew I’d have to wait until Thumper decided to tell me. He’s my richest client. I could be as patient as necessary.

I’d met Thumper Lee at the Ballroom a few years before. I’d seen one small ad in the Houston Press announcing a performance he would give on a Thursday night. I’d heard of him. He was a famous Texas blues musician. Up to the day I noticed that small ad, I thought he was dead. I’d seen a story or two that mentioned him being murdered in some mysterious way years before I was born. Out of curiosity, I went to the show expecting some kind of tribute performance, but it was the real deal. Before his last set, Thumper came out from backstage and talked to Jake who nodded in my direction. Thumper walked over to my table.

“Jake tells me you’re a lawyer man.”

“I am.”

“Stick around after the show. I want to talk to you about something.”

I stuck around. Thumper became my client, my first really good client since I’d left the law firm where I went to work right out of law school. Meeting him resulted in a lucrative relationship.

Like me, a record company thought he was dead. The company even won a Grammy Award for a collection of what they promoted as the lost recordings of Thumper Lee. Turned out they weren’t lost to Thumper. The record company owed him money, not just for that record, but for years of recordings.

It was a lot of money. We stirred up some trouble, and the publicity made his recordings even more popular. I helped him get what they owed him plus some damages. My fee paid for my boat, The Lonely Star, with a lot left over. I easily put up with his idiosyncrasies.

Thumper and Angelique Cambray came out of the backroom. She’d put on a pair of black parachute pants and a light blue jacket. He carried his two guitar cases. I stood when they reached my table.

Thumper introduced her, “Angelique, this is our lawyer, Samuel Locke. Sam, Angelique.”

She extended a hand. A thin sheen of perspiration on her face reflected the lights in the room. Her eyes were large and dark and beautiful. She smiled, but there was something off about her demeanor. Her shoulders slumped a bit, and her smile seemed forced. She looked directly at me when introduced. After that, she looked around nervously, not looking at one thing with focus. Despite the heat of the night and the effort of her dance, she crossed her arms, hugging herself as if cold. I got the impression meeting me was a command performance, and she’d rather be somewhere else. Once, when I met her and spoke to her at a meet and greet hosted by the Houston Ballet, she’d been much more relaxed and animated.

“A pleasure to meet you,” she said.

“Likewise. That was an incredible surprise. It was amazing.”

Her restrained smile grew a millimeter, and she quit looking at Thumper to look directly at me. “Thank you.”

“I’ve enjoyed your dancing before, but I’ve never seen anything like that.”

She nodded and Thumper said, “She has to go, but I wanted you to meet her.” Turning to her, he put an arm on her shoulder. They were the same height and eye to eye. “Are you going to be okay?”

“Yes.”

“You go where you told me you were going, and you stay right there until we call you. Understand?”

“Yes. Straight there.”

They hugged. She took a deep breath and looked like she was about to say something. She glanced at me and back at Thumper.

He said, “Go. It will be okay. Sam and I will get things fixed up. Don’t you worry. Sam, I’ll be right back. I’m going to walk her to her car.”

Something needed fixing. I’d thought Thumper called me about something related to his music, another recording or concert contract. But the wordless communication between Angelique and Thumper suggested something more complex and emotional than a business deal, something darker. I’d worked on a lot of business deals with Thumper without him ever inviting me to his place for the weekend. That, plus the fact that Thumper knew and had a relationship of some kind with a soloist with the Houston Ballet, was unusual. I knew something interesting was happening.

He returned and said, “What did you think?”

“That was impressive. Beautiful.”

“Yes. She is amazing.” He looked at Jake behind the bar and raised a finger. Jake nodded and raised a bottle of Wild Turkey.

“How did you meet Angelique?” I asked. “How did this thing get started?”

“Now, there’s a story. I need to fill you in about that.”

Jake delivered him a shot of whiskey and he downed it. “Come on,” he said. “I’m not going to do anything else here tonight. We’ll talk on the way up to the river.” He picked up his guitars and headed for the door.

Another group of musicians worked on stage, making tuning noises and doing sound checks. Thumper greeted a few people on the way out and signed two autographs.

He slid his two guitar cases into the back seat of my Range Rover, opened one, and took out a letter-sized envelope. He got into the passenger seat.

“Where am I going?” I asked.

“Head up toward Liberty. My place is on the river north of there. Up pass Moss Hill.”

I left the dirt parking lot of the Hall and drove through the Fifth Ward toward the highway.

“So,” I said. “You know Angelique Cambray.”

“Yeah, ain’t she something?” He was quiet for a moment, looking out the window and nodding his head at thoughts he finally shared. “When I was ten years old, I used to sit outside the Ballroom listening to the music. At twelve I earned a quarter a night on weekends clearing tables and mopping up spilled beer and whiskey.”

“Tell me more. How in the world do you know Angelique? What kind of legal work do you need?”

“I know her through family. You know, I used to walk along here to get home about this time of night. I’d walk into Houston, play on corners for tips, and walk home. It wasn’t really dangerous when I started doing that, but it got that way. It got so dangerous I went to New Orleans to be safe.” He laughed. “Can you imagine that? Moving to New Orleans to be safe.”

“I know it was really bad down here.”

“New Orleans had its problems, but at least its lawlessness had rules. For a while, there weren’t no rules in the Nickle.”

We left the Fifth Ward, nicknamed the Nickle, and got on the highway. Thumper seemed determined not to talk about whatever legal work needed doing. I didn’t mind. Instead, he talked about growing up in the Nickle, about the musicians he’d enjoyed, and about playing in blues clubs in Europe in the forties and fifties.

At the time of our lawsuit against the record company, I learned he’d spent time in Europe, disappearing from the States for a long time. But I’d never heard him reminisce in such detail about his history. I did that night as we traveled the dark highway leaving Houston. I treasured the moment and wished I could tape the oral history he shared. He got quiet as we entered Interstate Ten.

We weren’t on the interstate long before I exited to State Highway Ninety. We continued riding quietly without talking much until we crossed the San Jacinto River. Thumper finally decided to let me know a little more about what we were doing.

“You liked that dancing, huh?”

“Yes. It was a great idea to have a ballet done with your blues.”

“That was actually Angelique’s idea. She thinks we ought to take it downtown to the Wortham.”

“Good idea.”

“Yeah. It’s time for Thumperly to get into ballet.”

Thumperly Efforts L.L.C. is the name of the company we set up as Thumper’s production company.

“I’ll start studying up on what we need to do.”

He nodded. He had a look on his face, and he was holding that envelope, tapping its edge against his knee. I knew him. Something was coming about whatever was in the envelope, something about the tension between him and Angelique. I had to wait him out. We had time. He’d said his place was north of Moss Hill. The small town of Moss Hill was at least an hour away. I passed a sign advertising a service station just ahead.

“I’m going to pull off for gas. Want some coffee?”

“Sure. Coffee would be good.”

“Anything you want in it?”

“Nothing they’ll put in it.”

I filled up the Range Rover, took my travel mug from the console, and went inside. I filled my mug with the questionably named house blend and bought a large cup of the same for Thumper. I settled behind the wheel and handed Thumper his coffee. He opened his door and dumped out some of his coffee. Taking a flask out of his jacket he put a healthy dollop of whiskey in his cup. My truck smelled like hot coffee and whiskey.

“Want some?” He offered me the flask.

“Nope. I can just breathe it in. I hope I don’t get stopped.”

“Me, too.”

Back on the highway, there were fewer and fewer lights. We drove into the darkness, the air conditioner holding off the humid heat of summer. After the lawsuit with his record company, Texas Monthly Magazine did an article profiling him. They called him a Texas legend. Thumper frustrated the writer who wanted to do a feature-length article about his history, his disappearance, and his re-emergence. Thumper would not cooperate with any discussion of his past. The deadline loomed, and the article ended up being a one-page profile accompanied by a really nice photograph. His record sales in Texas bumped up a bit after the article appeared.

It felt good driving in the dark of East Texas with a certified Texas legend. I felt lucky to have the moment. The scent of whiskey and coffee fit the moment perfectly.

“You know what,” I said, “give me a little. Very little.”

I held my cup out, and he topped off my coffee with a splash of Wild Turkey from his flask.

“Hey, what if I want to give Angelique some of Thumperly? I can do that, right?”

“Yes, you can do that. What exactly is it you want to do?”

“Take care of her.”

Was he falling prey to some crazy attraction to her? Was she after his money? Things were starting to sound strange. Something was up.

Before I could formulate a way to probe his motives, he said, “I need you to represent her about something.”

“What would that be?”

“Here, take this.” He held the envelope my way.

“What’s that?” I kept both hands on the steering wheel. I did not want to touch the envelope until I knew what was going on.

“It’s a check for ten thousand dollars and a letter from her asking you to be her lawyer.”

Ten thousand dollars. Uh oh.

“Thumper, I cannot agree to be her lawyer without knowing what’s going on.”

“That’s what I’m going to do up at the river. Fill you in on what’s going on. But we need that lawyer secret thing in place.”

That lawyer secret thing. Uh oh.

“If I’m supposed to represent her, I have to talk to her. Not you.”

“You will, but everything I do from now until the day I die will be to take care of her. In fact, I need you to change my will up so she gets everything.”

Uh oh.

“We’ll talk about it. Thumper, who is she to you? What’s going on?”

“She is my granddaughter. Take the check. It’s mine, not hers.”

I took the check. Thumper was the grandfather of Angelique Cambray. That surprised me as much as any one thing could. The weekend promised to be very interesting.

“We’ll talk about it tomorrow,” he said. “I’m tired. Wake me up when you get to Moss Hill.” He leaned the seat back.

We drove silently into the dark.

By that time, they’d fed the dead guy to the alligators.